September 6, 2021

As the vulnerabilities of and complex challenges facing the small states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) have become even more pronounced during the novel coronavirus—SARS-CoV-2—or COVID-19 crisis, novel collaboration has emerged between countries of this regional grouping and their African counterparts. The agreement that parties arrived at in respect of the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines through the African Medical Supplies Platform (AMSP), as well as bilateral arrangements, which some Member States pursued with the support of CARICOM, is demonstrative of increased momentum for an enhanced CARICOM-African Union (AU) partnership. The AMSP COVID-19 vaccines procurement initiative, which has symbolic and practical value, brought CARICOM-AU relations to the forefront of CARICOM foreign policy discussions. The AU has scored political points in CARICOM, not least because of the public attention that this initiative has garnered, opening the door for another kind of vaccine diplomacy. Beyond the immediate benefits to CARICOM, amid a fraught vaccines rollout process for developing countries, this initiative opens possibilities for new cooperation opportunities between CARICOM and the AU under the auspices of summitry. CARICOM is a demandeur regarding this foreign policy track.

One of the CARICOM establishment experts and now retired diplomat notes: "CARICOM, at least some member states, seems keen to pivot towards a more Africa-centric foreign policy." It is not as if Africa has become the primary focus for CARICOM, although recent diplomatic overtures gave new impetus to deepening ties than was previously the case. CARICOM's political agenda towards the AU is of a sort that has opened up a diplomatic path not previously taken: CARICOM-AU summitry. That agenda has assumed increasing prominence in CARICOM foreign policy debates, as scholarly circles hasten to bring academic focus onto associated cooperation dynamics. What explains CARICOM's foreign policy posture towards deepened relations with the AU, revealing as it is of a strong interest in summitry? This article identifies and explores CARICOM's core interests, examining the emerging currents of the wider interrelationship between the Caribbean and Africa, which represent an enhancement of diaspora-centric discourses and traditional international cooperation relationships. This article's primary aim is to analyse the main drivers of and hopes for this new era of CARICOM-AU relations, having regard to a CARICOM perspective, showing that for CARICOM political elites summitry's main drawcard is to reconceptualise those relations. It sees the scope of salient diplomatic and political agendas of CARICOM Member States as now so great as to connect to keen support for such summitry, particularly in areas where CARICOM and African interests converge, becoming mutually reinforcing.

CARICOM-AU relations are increasingly the subject of scholarly debate, which picked up in Caribbean academic circles over the last two-plus years. A new generation of Caribbean area and international studies scholars have been at the forefront of this latest wave of research, as Caribbean-African relations are gaining new traction. However, Caribbean practitioner communities were among the first to draw attention to emergent CARICOM-AU summitry, which Caribbean scholarly communities have hitherto largely overlooked. In African affairs circles, academic studies on contemporary African summit diplomacy also have not considered the summitry-based trajectory of the recently embarked upon quest for deepened cooperation on CARICOM-AU relations. Drawing on primary and secondary sources, the article helps fill this gap, contributing to the extant literature. Written with primarily Caribbean and African policy-makers in mind, it is an attempt to provide one of the first systematic scholarly analyses of summitry in the making as regards CARICOM-AU relations.

The article proceeds as follows. First, it combines a sketch of older Caribbean-African relations with more recent cooperation-related undertakings, framing mooted CARICOM-AU summitry and its precursor diplomatic milieu by analytically situating both regions in international affairs-related high politics. I show that some recent foreign policy stances of a handful of CARICOM Member States provided early, if incomplete, signals as regards the regional push for a deepening of CARICOM-AU relations. Second, this article delves into the fundamental issue of how to cast Caribbean-African relations while also taking a closer look at summit diplomacy and the main drivers behind African and Caribbean countries' foreign policies. Third, and from a CARICOM vantage point, it pinpoints the role of geopolitical and geo-economic dynamics in the making of summitry with the AU. In the case of the geopolitical dimension, the article highlights recent systemic shifts in relations between the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS) and the European Union (EU). The article also examines geo-economic shifts germane to the Africa axis of CARICOM Member States’ foreign policies, underlining the associated value that CARICOM attaches to the summitry enterprise. The article concludes with a look back at core lines of argumentation, along with a look ahead at the practical implications of the COVID-19 crisis and other conditions vis-à-vis the prospects for deepened CARICOM-AU relations.

Caribbean-African Relations in Retrospect and Prospect

Caribbean-African relations are wide-ranging, with scholars engaging the subject from various disciplinary angles. For example, a select group of eminent Caribbean intellectuals renowned for their work as historians in this area of study (among them the late Eric Williams), who one scholar associates with a "Caribbean School" of luminaries, has contributed immensely to our understanding of the transatlantic slave trade and European colonialism and their legacies. The article shines a light on contemporary Caribbean-African relations, deploying the scholarly lens of international relations (IR). A key element in those relations is the advent and evolution of the then-African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP), which catalysed the said relationship. Over an almost five-decade-long period to date, there has been a qualitative shift in those relations. They also took shape in the United Nations and the Commonwealth, among other international fora. Within the broader history of their relationship, Caribbean and African political elites stood shoulder-to-shoulder on the global stage in respect of important issues of the day, such as decolonisation and the anti-apartheid movement. Indeed, the Caribbean and African interests have co-mingled in key multilateral fora like the OACPS, formerly the ACP, "an aspect of African and Caribbean international cooperation" that I will return to further along in this article. The ideological currents and conflict of the Cold War also loomed large in broader discourses around statecraft, which were not always cooperative.

Rising powers' agendas, unfolding over the last twenty-plus years, in respect of either "revising or upholding" what scholars call the Pax Americana-hinged "liberal world order" (with the United States (US) as its guarantor) are also salient to both the Caribbean and Africa. This at a time of renewed great-power competition, owing to the People's Republic of China’s (PRC) growing geopolitical preponderance and the striking contestation that befell the US power dynamic in the oft-idealised liberal international order. In this international (polarity) context, the (Anglophone) Caribbean is “system ineffectual,” adopting “optimal ... strategic behaviour” pertinent to such secondary states in the face of long-term Sino-U.S. strategic competition. For example, only five of the 14 sovereign CARICOM Member States extend diplomatic recognition to the Republic of China (ROC or Taiwan). (Analysts have sounded a cautionary note about the risk of Latin America and the Caribbean’s entanglement in increased geopolitical competition, which Beijing has made inroads into via the expansionary Belt and Road Initiative that will likely be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.) Those CARICOM countries are also calibrating cooperation-based responses to the influence-driven external action of a complementary global actor in the U.S.-led international order: the EU. As for Africa’s foreign policy orientation, given the varying interests and priorities of the continent’s sovereign states, it has complex relations with the world’s pre-eminent normative power and with emerging powers like the PRC because, not in spite, of decades of America’s relative hegemonic decline.

With some rising powers’ increased contestation of the institutional and normative determinants of the Euro-Atlantic global order, CARICOM’s policy-makers are eager to change the course and stance of CARICOM-AU relations. The key concern, according to some CARICOM foreign policy insiders, is the hope for summitry as an instrument to advance those relations, having regard to rising powers coming into their own (e.g. key actors in Africa) and Western (e.g. European) interests that are marshalling partnership-related processes in response.

All the while, the Caribbean and Africa’s relationship has expanded to more policy fields, although “the level of direct interaction between [them] in the economic ... sphere has [traditionally] been low.” Those relations have certainly become a high profile foreign policy strategy. Notably, in July 2018, the then-Chairman of CARICOM the Most Hon. Andrew Holness, Prime Minister of Jamaica, paid an official visit to Namibia and South Africa. Subsequently, in August 2019, the President of Kenya, H. E. Uhuru Kenyatta, paid state visits to Barbados and Jamaica. During those visits, the leaders gathered gave an undertaking to work towards a CARICOM-AU Summit. At the time, the CARICOM Secretariat—the administrative arm of the Community—also called attention to the intention of CARICOM and the AU to sign a Memorandum of Understanding establishing a framework for engagement and cooperation.

Building on these developments, in December 2019, on behalf of her regional colleague Heads of Government, Prime Minister of Barbados, the Honourable Mia Amor Mottley, took part in a most auspicious moment in this new era of CARICOM-AU relations. It was an official ceremony held in Nairobi, Kenya, on the margins of the 9th ACP Summit of Heads of State and Government, marking the occasion of the handover of office space intended for a joint CARICOM diplomatic mission. Setting aside dedicated space for such a diplomatic mission is regarded as a positive gesture from both parties, indicating a willingness to advance the relationship between both regions. Reacting to these developments, a source in CARICOM foreign policy circles said, “Hopefully, CARICOM countries take advantage of the opportunity.” (Having regard to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as the hub for the AU Commission and the Permanent Representatives Committee, another source suggests that this African city ought to be on CARICOM’s diplomatic radar.) A notable development is that the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, Honourable Gaston Browne, who is the current CARICOM Chairman, recently announced that a CARICOM diplomatic mission would soon open in Nairobi.

These events unfolded against the background of CARICOM and the AU’s cooperative convergence, which has since experienced a fillip on account of some CARICOM states having recently proceeded to establish resident diplomatic representation on the African continent. Barbados’ leadership confirmed the establishment of that country’s diplomatic presence in Ghana. Barbados has also expanded its “diplomatic footprint” to Kenya, with some other Caribbean leaders—including those of Suriname and Saint Lucia—remaining upbeat about their respective states establishing diplomatic missions in Africa in the near future. All the while, CARICOM and African countries enter into formal diplomatic relations with increasing frequency.

A few years ago, individual members of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) established the joint diplomatic mission of the Embassies of Eastern Caribbean States to the Kingdom of Morocco (ECS Embassies) in Rabat. It is one of the more recently established Caribbean country missions in Rabat, along with the Embassy of the Republic of Haiti, coming against a backdrop where a few CARICOM countries established diplomatic missions in some African countries stretching back decades. Jamaica is one such country, with a diplomatic presence in Nigeria and South Africa, respectively.

On the cusp of the age of COVID-19, it had not gone unnoticed that as part of an intensifying trend of high-level Caribbean-African diplomatic engagement Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Dr. the Honourable Keith Rowley, paid an official visit to Ghana in March 2020. He met with that country’s President, H. E. Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, affirming his country’s commitment to strengthening bilateral ties with Ghana.

As these episodes of leadership-level engagement show, Caribbean-African relations are a top priority for Caribbean leaders and policy-makers, who have stepped up Africa-directed diplomacy and statecraft more than at any other time in the post-Cold War era to date. From 2019 onwards, the tempo and orientation of CARICOM-AU relations have changed markedly. For a brief period in 2020, as mainly official documents highlight, this pace of engagement continued unabated. Then the coronavirus pandemic took hold, compelling states to re-evaluate the breadth of their foreign policy priorities, seemingly putting a damper on this new political qua diplomatic trajectory. The postponement of the CARICOM-AU Summit, originally carded for 2020, stands out.

Irrespective of this pause, a defining feature of the contemporary dynamics of Caribbean-African relations is CARICOM’s push for summitry, which remains a work in progress. While the advent of the pandemic took the convening of the summit off course, preparatory work continues behind-the-scenes, through a combination of bilateral diplomatic channels and regional integration organisations like the CARICOM Secretariat.

At the Twenty-Fourth Meeting of the Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR) of CARICOM, regional Foreign Ministers deliberated on relations with the AU, “reaffirm[ing] their readiness for a CARICOM-AU Summit as soon as practicable.” According to CARICOM’s leadership, the CARICOM and AU sides remain engaged with one another in respect of laying the groundwork for their summit. In a sign of strong and sustained political will in the CARICOM context regarding this summit, a prominent voice in regional leadership signalled the way forward for this first-of-its-kind forum; although, recent official indications are that it has indeed been postponed sine die. As this article was in press, the CARICOM Secretariat published a statement advising that the inaugural CARICOM-Africa Summit will be held virtually on 7 September 2021.

The aforementioned AMSP-based collaborative episode and leadership-level diplomatic engagements that foster summitry are emblematic of a contemporary shift toward enhancing CARICOM-AU relations that have been years in the making, all of which renews our attention to a key conceptual matter: if Caribbean-African relations have shown anything, it is that they are multi-pronged and periodically assume a high diplomatic profile. That said, we must go beyond this narrow focus, further distilling Caribbean-African relations and other issues.

How can we cast Caribbean-African Relations?: Understanding CARICOM’s Summitry-seeking Politics, with attention to Fragmented African Power Dynamics

At first blush, the phraseology Caribbean-African relations may seem rather straightforward, but juxtaposed in the history books, it is complex, not least because the following question invariably arises: to which prong of the Caribbean regional configuration is one referring? Is it the Anglophone, Francophone, Spanish, or Dutch-speaking parts, or perhaps some combination thereof? The Caribbean is a contested term, temporally the subject of shifting meanings and conceptually the subject of wider debates at the heart of political geography.

Cuba is one such example. Cuba, whose long-standing relations with Africa are widely recognised as “significant,” is part of a wider regional prong vis-à-vis the Caribbean. Cuba’s influence in hotspots on the African continent during the Cold War is such that it has a starkly different relationship with several African states than, say, most CARICOM states. To this day, owing to that sui generis history, Cuba plays “host [to] twenty-two African embassies, more ... than any other Latin American or Caribbean country.” Cuba-African ties, which fall outside the scope of this analysis, are constitutive of a long-standing and highly political relationship.

In the case of summit diplomacy, some scholars of international politics characterise it as taking place at the very highest levels, “hav[ing] very practical effects,” with its distinguishing feature being the involvement of political leaders. Others trace summitry, a particular “type of diplomacy”, as existing over many centuries. The available literature is large. Among those research strands that are of particular interest is scholarship on ‘global summitry’, which is ostensibly taken up with a multiplicity of matters as regards the contemporary “global order”.

With the rise of increasingly complex and interconnected challenges, which require expansive international cooperative approaches, broader scholarly debates on summit diplomacy and the Global South have emerged. Insofar as that literature on summitry has not yet reconsidered its over-reliance on case studies featuring large Global South countries, there is a paucity of scholarly work on small states. Summitry pertaining to CARICOM is a case in point, having been the subject of just one notable scholarly work in recent years. CARICOM’s and its members’ diplomatic steps toward CARICOM-AU summitry have been traced herein; yet, the picture is incomplete. We have to consider the foreign policy context.

From an AU perspective, Kenya has been the leading voice in this most recent chapter of Caribbean-African relations. President Kenyatta’s 2019 visit to the Caribbean came to signify his strong commitment to a new era of Caribbean-African relations. The politics of that visit and President Kenyatta’s wider support for AU summitry with CARICOM, pursuant to Prime Minister Mottley’s (among others’) backing of such high-level diplomacy, were at the time partly linked to his country’s now successful bid for a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). According to sources, the calculus of that trade-off (at least for Kenya) now no longer holds. Over two years on, it continues to change in light of the shifting political winds in Kenya vis-à-vis the 2022 general elections and President Kenyatta’s vested interest in what his legacy ought to be. With the foregoing in mind, in the best tradition of foreign policy scholarship, the following question arises: what do these domestic political currents portend for Kenya’s CARICOM directed foreign policy and, more so, the AU delivering on this summitry promise? As is the case with such endeavours, progress hinges on politics on the domestic front but also an alignment of interests at the interstate, Africa-based level.

Even though Nigeria’s leadership credentials in a sub-Saharan African context have come under scrutiny recently, along with those of South Africa, with the latter characterised by some academics as a “fragile hegemon,“ in the broader leadership conception of Africa, it matters where these two countries stand on a spectrum of African affairs issues of the day. Yet, this remains unclear vis-à-vis official positions on prospective CARICOM-AU summitry. What is apparent is that official discourses on South African foreign policy, for example, adopt a relatively expansive stance pertaining to Cuba, with the broad idea of the African diaspora framing its relations per CARICOM. Academic soundings are not of much help either. Complicating matters is the “changing power capabilities” among some African countries, which have competing foreign policy concerns, influence and notions of steps required vis-à-vis attaining political agendas. Those cleavages between powerhouse African countries are stark regarding their respective relations with key third states, bearing in mind foreign policy coordination shortcomings.

What of CARICOM Member States’ respective foreign policies? Their foreign policy approaches have been the subject of detailed academic study, with scholarly attention extending to their post-Cold War positioning. Such approaches can broadly be understood along the lines of “[t]he foreign policies of small states [that] are often dominated by economic considerations both in relation to the general lack of diplomatic resources and the fact that economic development is the main goal of foreign policy.” The Caribbean small states context: “[t]here is one common domestic concern that influences foreign policy [namely] the state of the domestic economy.” CARICOM Member States’ foreign policies, pursued in line with national interests, also tie to: (i) harnessing processes and institutions of multilateralism to amplify those sovereign states’ voices in international politics in deference to their “unique experiences;” and (ii) a common set of aspirations per the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas establishing the Caribbean Community including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy.

With regard to the CARICOM bloc’s steps in the direction of CARICOM-AU summitry, what stands out is the promotion of “mutually beneficial relations among the Member States.” This premise has liberal IR overtones. The conduct of foreign policy may not always align in this manner, though, making for a mismatch in interstate foreign policy-oriented ‘coordination’ where the national interest takes precedence à la IR-based realist qua realpolitik considerations. The fact remains that the concept and wider context of “a Community of Sovereign States” frame the ‘coordination’ of Member States’ foreign policies. This is the subject of debate in CARICOM foreign policy circles, with some having determined that it is the taproot from which “CARICOM’s … influence in international fora [has been] minimise[d] rather than maximise[d].” For them, “CARICOM must do a better job in forging and maintaining a regional consensus, finding a common position that all member states can support, even if it is not the best position for some, but is acceptable.”

In sum, the historical picture in relation to the coordination of CARICOM Member States’ foreign policies has been the subject of much reflection, with CARICOM watchers acknowledging that long-standing differences along with more recent ones have put up barriers in that regard.

However, a senior member of CARICOM’s foreign policy establishment cautions that “placing emphasis on the difficulties of CARICOM foreign policy coordination [is a misconceived notion].” This source maintains, “[t]here are far more examples of success than of it not working [and] the CARICOM-AU Summit proposal is one of those.”

The changing context of geopolitics and geo-economics has a bearing on CARICOM’s move toward summitry with the AU, which is emblematic of the regional grouping’s overarching strategy to overcome smallness: securing multiple partnerships as a potential source of advantage in international bargaining or diplomacy. This is critical especially for the Caribbean’s relations with the EU, a cornerstone of regional states’ respective foreign policies. These developments are the subject of the following section, as are the Caribbean’s attempts to manoeuvre accordingly, with an eye to Africa.

Geopolitical and Geo-economic Factors in Shaping CARICOM-AU Summitry

The OACPS and OACPS-EU Dimensions

COVID-19 response and recovery is a central preoccupation for CARICOM policy-makers, raising a degree of uncertainty regarding the prospects for enhanced diplomatic engagement across certain bilateral and multilateral fronts. Notwithstanding, at this crucial moment, CARICOM policy circles are pursuing targeted opportunities to deepen CARICOM-AU relations alongside high-level CARICOM-AU engagement. What is apparent is that some in CARICOM’s political leadership are advancing key national priorities through a foreign policy tie-in with the AU, building political capital along these lines. This undergirds the broader shift in the character and direction of CARICOM-AU relations, as CARICOM faces a new international politics-related reality. One reason this CARICOM-AU political dynamic has become more prominent is that the ACP, which became the OACPS on April 5, 2020, “has not been the strategic global player that it planned to become when the [Cotonou] Agreement was negotiated.”

In this regard, the dominant factors that condition CARICOM’s intensified Africa gaze are two-fold. There is a recognition that the EU, whose institutional set-up and political dynamics tend to be underappreciated, continues to place considerable importance on its relationship with Africa. The EU and Africa have a high-profile partnership with a wide-ranging agenda that has significant financial backing, which CARICOM could potentially tap into going forward. Such a likely strategy is not without its risks, as AU-EU relations are not without their challenges. Some suggest those relations are at a crossroads, just as “[t]he ACP-EU partnership has gradually evolved from a preferential relationship towards a reciprocal, interest-driven partnership.” This has taken place alongside the evolution of the EU bloc’s internal balance, caught between the particularities of the politics of the Western and Central/Eastern European sub-regions. This corresponds with interrelated differences, which are seemingly peripheral to some scholars, who overemphasise points of policy convergence on a fundamental aspect of the EU’s foreign affairs: its relations with the OACPS. European integration, which “[i]s the outcome of a struggle for power among competing hegemonic projects,” figures prominently in this latter regard.

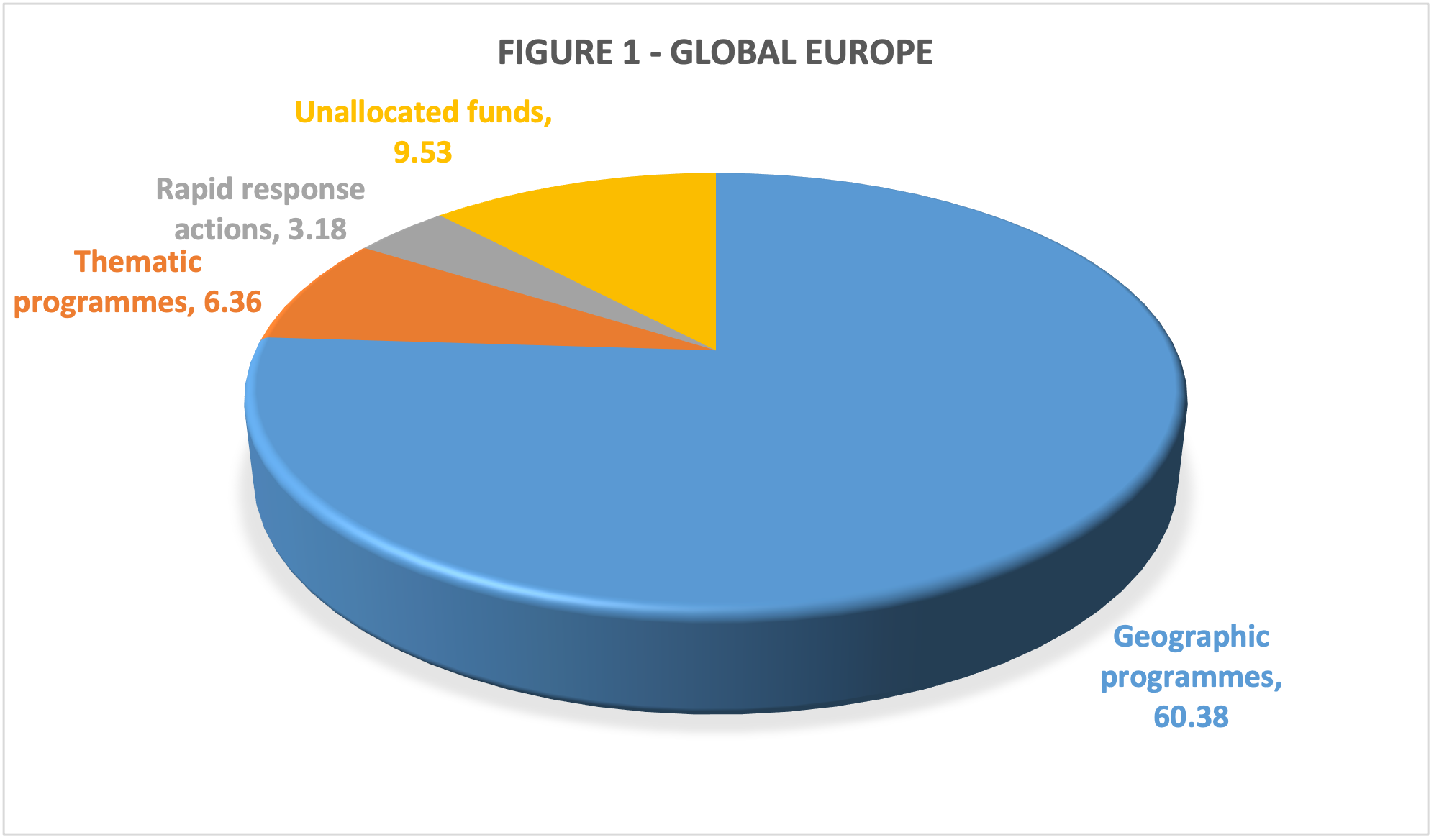

The impact of the changing nature of these dynamics on EU-OACPS relations meant, inter alia, the EU dispensing with intra-OACPS ring-fencing. A more significant development is the new Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) or Global Europe, which in the context of the 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework (MFF) “will support the EU’s external action with an overall budget of €79.5 billion in current prices.” NDICI merges several instruments, focusing on “cover[ing] … EU cooperation with all third countries.” This new instrument comprises elements illustrated in Figure 1 (below); allotted to each are financial resources in the billions of euros, as set out in this chart.

Source: Author, drawing on data from European Commission documentation.

With regard to NDICI-related ‘unallocated funds’ (highlighted in Figure 1), they could “replenish” Global Europe’s two programmes and the rapid response actions in the vein of a contingency, while also addressing “new needs or emerging challenges and promot[ing] new priorities.” Regarding NDICI geographic programmes, the following obtains: the Neighbourhood (allocation: at least €19.32 billion), sub-Saharan Africa has its own allocation (at least €29.18 billion), Asia and the Pacific (allocation: €8.48 billion) and for Americas and the Caribbean (allocation: €3.39 billion). The Americas and the Caribbean allocation represents 5.6% of NDICI geographic programme resources. Policy debates over the Caribbean’s positioning in this manner revisited long-running considerations, having regard to what is perhaps the most significant combination of shifts in Caribbean-Europe relations, paying close attention to the new logics of the post-Cotonou framework. Indeed, the then-CARICOM and CARIFORUM Secretary-General, Ambassador Irwin LaRocque, acknowledged in 2019 that post-Cotonou negotiations constitute “an opportunity to forge an agreement to reflect changing times, new challenges and current developments.”

Reflecting on the post-Cotonou schema, a former high-ranking functionary at an international organisation said, “The battle for the Caribbean will be negotiating and finalising its portion of available development resources.” Another analyst notes: “For the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM), the challenge is not just the extent of accessibility to the resources, but also what will obtain regarding co-management or CARIFORUM control.” This reality is front and centre for the political directorate, judging by regional leaders’ recent pronouncement on efforts to put things in place regarding a post-Cotonou framework-related Caribbean Multi-Annual Programme.

Less widely appreciated, though, is that NDICI “marks a profound transformation of EU development policy and spending,” given that the Union’s development finance now falls under its budget, with a view to serving a broader range of interests at a time when the post-1945 international order is in flux.

With the EU’s move to NDICI, doing away with the European Development Fund (EDF), which had been in the crosshairs for some time, the OACPS’s strategic positioning has been weakened. Consider that the advent of this now 79-member strong grouping hinged on two broad objectives, one of which was taken up “with the implementation of the Lomé Convention ... ensur[ing] [inter alia] the realisation of the objectives of that convention.” Indeed, the negotiation of the first iteration of the Lomé Convention between the European Economic Community and the ACP, as they then were, was “central to the emergence of the [latter] group itself.”

In effect, the budgetization of the EU’s development finance heralds a new approach to the development aid-related bedrock of the EU-OACPS partnership. Instructively, “aid, which for a long time [was] the lifeblood of the partnership, [has] to a large extent been moved out of the partnership.”

Moreover, the recently inked post-Cotonou deal, which the EU began to prepare for in 2014 and the EU and the OACPS started to negotiate in 2018, lends to “new impulses … emanat[ing] from a two-tiered framework that allows for the framing of general policies at the All-OACPS/E.U. levels, and their specific articulation in the respective regional protocols.” Expanded partnerships are now possible, transcending the erstwhile EDF-established status quo. Given the complexity at play, a direct line to Africa at the highest diplomatic level is ideal for CARICOM.

CARICOM and its Member States have made a concerted effort to reboot their diplomatic engagement with Africa in a world order in the midst of consequential power shifts, of which a rising Africa forms a part. This is a potentially crucial step, considering Western powers’ interest in CARICOM has waned. Precisely because CARICOM is attracting less attention in the West, concomitant to an opposite trend in respect of the attention that Africa is currently garnering at the highest levels, high-level EU-AU relations can potentially open space for expanded diplomatic engagement of CARICOM with the EU in discrete policy areas, e.g. climate change.

Given the AU’s growing geopolitical and geo-economic influence, more than ever, CARICOM has consistently cast its foreign policy gaze at that 55-member bloc. For CARICOM, the AU is a crucial plank in its bid to help achieve and safeguard the interests of its members. Consider that CARICOM’s leadership has been at pains to underscore that “the multilateral architecture has been under increasing strain [and] [g]eopolitical competition in our multipolar world has increased [; the contention being that] CARICOM … must bolster its relations with like-minded states and continue to advocate for multilateralism.”

A senior CARICOM foreign affairs analyst is “still to be persuaded that CARICOM is ready to implement such a strategy effectively,” suggesting this view permeates many quarters.

Though partial, the geopolitical dynamics outlined above are an important rung of CARICOM’s pivot to summitry with the AU. The other set of dynamics is of a geo-economic nature, as set out below.

CARICOM-AU Summitry and the AfCFTA Factor

With the exception of CARICOM’s commodity exporters (namely, Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago), over the past several years, CARICOM countries “have been characterised by a stagnant performance in goods exports,” with those countries’ having a mixed record of success regarding services exports. It is important to note that CARICOM is underperforming with respect to trade in goods because of regional states’ structural and size-related limitations. Many CARICOM countries have lost ground in traditional export markets, with Caribbean foreign and trade policy experts having long counselled that the bloc’s decision-makers needed to come to terms with new “trends in globalisation... [and a] world economy [that] has already changed [with] far-reaching implications [for said countries, such that] it cannot be business as usual.”

This narrative provides an indication of why, in pledging in December 2019 to work closely with several African stakeholders to “make real the first CARICOM/Africa summit,” the then-incoming Chairperson of CARICOM drew attention to the need to generate more opportunities for the region’s business community. In the past, there have been business-to-business engagements. While a handful of Caribbean conglomerates have explored business ventures in certain African countries, some more successfully than others, “[t]here is much work to be done in promoting trade and investment between CARICOM and African countries.”

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could provide a potential stepping-stone to deepen CARICOM-AU commercial and trading relations. The AfCFTA will pave the way for Africa to become one of the world’s largest free-trade areas, also presenting economic opportunities for regional actors beyond Africa. Signed on March 21, 2018, and entering into force on May 30, 2019, the AfCFTA is a central aspect of several flagship programmes/projects of the contemporary development agenda of the AU, Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. The Agenda 2063 itself is a bold, new pan-African initiative adopted in January 2015.

The AfCFTA is emblematic of a renewed commitment to industrialisation at the highest levels of African development policy-making, harnessing a broad integrationist agenda. This story’s subtext: the expectation is the AfCFTA will expand intra-African trade and industrialisation spanning the eight AU-recognised Regional Economic Communities, which are the ‘building blocks' of an envisioned superposed African Economic Community.

Regarding foreign policy thought in the Caribbean, which places a premium on multidimensional cooperation imperatives, prospective commercial diplomacy wins associated with the AfCFTA and attendant cooperation with Africa likely also factor into CARICOM’s embrace of the CARICOM-AU Summit initiative. Consider that, while they are highly dependent on trade, “CARICOM [states have] been underperforming on trade—compared to other developing countries—before and after the 2008-10 recession.” The key attendant characteristics of this kind of performance are, inter alia, “low participation in value-added chains ... and low levels of market diversification.”

There is clarity with regard to CARICOM’s external trade scenario, snared as it is in wider structural imbalances and lack of competitiveness, which in combination figure as a leading cause of these economies’ long-standing lacklustre economic growth. That said, it is not entirely clear that CARICOM members’ emerging diplomatic initiatives will lead to meaningful increases in trade vis-à-vis the AU in this prevailing economic setting.

One of the CARICOM establishment experts and now retired diplomat is of the view that this lack of competitiveness, which has been underlined once again, “is one of the major constraints holding back CARICOM exporters, and improved market access will not overcome that problem.” Under such circumstances, this former technocrat contends, “[w]e need to address the supply side constraints before we can convert market access into market presence.”

What is more, CARICOM countries’ “high economic dependence” on “transport, trade and tourism” has left them especially exposed to the COVID-19 crisis’s knock-on effects, which have also spurred a dramatic and sustained decline in the value of their goods exports. Between January-June 2020, the value of CARICOM goods exports dropped precipitously. In addition, there are worsening low growth/high debt realities. In a situation where “remittances are a significant source of inflows of financing” for several of these countries, the pronounced fall in inflows of remittances has contributed to the sharp contraction of these economies.

In assessing long-term considerations for building greater resilience for these countries, some development experts underline the importance of “find[ing] new markets.” Others reaffirm long-standing calls for diversification, including the expansion of trade in the goods and services sectors “or mov[ing] up the value chain.” Still, others suggest that finding new markets will not solve the prevailing supply-side problems, as the region’s producers need to become more competitive and genuinely export-oriented regardless of the market. In the specific context of prospective CARICOM-AU commercial relations, those experts see geographic distance and logistical/distributional issues as standing in the way of closer ties. While acknowledging that there is scope for franchising of major Caribbean companies in African markets, one expert views CARICOM-AU geo-economic dynamics as having to contend with African countries’ tendency to look toward European and Chinese markets, while CARICOM countries tend to look toward the UK and North America.

While there has been a recent uptick in interest in expanding CARICOM’s trading relations with Africa, CARICOM-Africa economic relations are still a long way from realising their optimal level. It is noteworthy that “the Caribbean enjoy[s] a trade surplus.”

Concluding Observations and Practical Implications of the COVID-19 Crisis Issue, among others

One of the distinctive features of contemporary CARICOM-AU relations, which may finally be coming of age, is the largely successful official attempts to formalise a cooperation-driven relationship on a sustained basis. Bilateral diplomatic engagements also enjoy increasing appeal among heads of government, laying the groundwork for summitry to frame CARICOM-AU relations. From a CARICOM perspective, the available evidence suggests that the factors leading to and the logic of this shift are twofold, which this article draws out. This planned summitry will be a key channel for the bloc to better navigate a complex amalgam of geopolitical and geo-economic dynamics, as well as associated challenges, before it. As important, this indicates that summitry lends itself to CARICOM’s deepened relations with like-minded states and strengthened multilateralism, which taken together are key ingredients for such small states’ effective positioning in international affairs, capturing well the stakes for CARICOM in the anarchic international system.

The article has argued that while the establishment of CARICOM-AU summitry is a work in progress, it represents an opportunity for the two sides to transform their political and diplomatic agenda. The article examined the shift (in train) to summitry in CARICOM-AU relations to support this argument. It analysed why this prospective summitry matters for CARICOM, against a wider backdrop of shifts pertaining to aspects of the bloc’s global partnerships and its global positioning. The article identified opportunities, as well as challenges. There is reason for guarded optimism. Some analysts of CARICOM are circumspect in their view of prospective CARICOM-AU summitry, arguing, “the value of such an initiative depends on the level of importance attached to same and the subsequent commitment to achieving tangible outcomes.” One key insight is that “[t]here have been ACP summits for decades and the participation from both CARICOM and African countries has been poor.” One source suggests that, at this stage, whether the CARICOM-AU Summit initiative will stimulate greater engagement is an open question. It is also worth noting that some Africa analysts have misgivings about the ability of the AU and its member states to coordinate engagement with partners, pointing to challenges in negotiating common African positions.

This article also calls attention to the provision in the bloc’s constituent document pertinent to COFCOR’s coordination of CARICOM Member States’ foreign policies, suggesting that members’ respective foreign policies are subject to nuanced priorities and execution. Simply put, given that CARICOM members set and pursue priorities in line with their own national interest, fast-tracking a revamped Caribbean-African relationship will likely not command the same degree or type of policy effort among all members of the CARICOM bloc. Further, the impact of capacity and resource constraints on the optimal performance of such a new relationship cannot be overstated.

In closing, inasmuch as this article has added a new scholarly perspective on Caribbean-African relations, it has research limitations. It reflects single case research, focusing in the main on CARICOM. An AU perspective on CARICOM-AU summitry is of interest to scholarly and practitioner communities, too, and it ought to receive equal research coverage going forward.

Under the present COVID-19 circumstances, it would be remiss of me not to also reflect on the pandemic’s potential impact on efforts to advance CARICOM-AU relations. Challenges have arisen regarding, inter alia, the conduct of multilateral diplomacy and summitry in the virtual environment. While digital diplomacy is a reality, increasing accessibility and frequency of interactions, core dimensions of in-person summitry are “undercut” or lost in an online dispensation. As regards engagements between Caribbean and African leaders from mid-2018 to early 2020, geared towards advancing on a new era of CARICOM-AU relations, what perhaps stands out the most is that they were face-to-face meetings. In a currently ‘socially distanced world’, virtual diplomacy may not lend itself to the kind of relationship-building required to cinch those relations.

In addition, any summitry-related dividends in the short- to medium-term for CARICOM’s private sector should be weighed against the current backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, considering that it “has substantially altered the context for cross‐border business.” It is also the case that, given the shared threats faced by the Caribbean and Africa stemming from the COVID-19 crisis, CARICOM-AU summitry could present an opportunity for collaboration in and serve as a plank for the Caribbean coronavirus diplomacies in respect of pandemic-related responses and recovery. Will that strategy pay off? It is hard to say. Even though the AMSP is an important achievement in its own right, it is not a predictor of the success of more wide-ranging cooperation on the COVID-19 front. However, the AMSP is a rebuke of vaccine nationalism, perhaps even a “COVID ‘legacy good’.”

Two other cautionary notes are in order. Summitry’s influence must be placed in context: it “only directly touch[es] a relatively small proportion of international interactions.” Ongoing diplomacy, building relations, finding common ground and working together to advance mutual interests are the province of Foreign Ministers and their Ambassadors. While heads of state and government bring the high profile and influence of their Office, the actual cooperation-based exploration, manoeuvring and the like are done by Foreign Ministers, who set the agendas and prepare the summits in the first place. Accordingly, and in light of their advisory roles, it behoves diplomats and functionaries in state and regional bureaucracies in CARICOM to develop greater expertise in African affairs.

Put differently, summits do not by themselves constitute a holistic foreign and trade policy. A summit is a high profile diplomatic tool. A lot of preparatory work is required in advance to make summits meaningful. Serious follow-up by public and private sector players is required to maximise any summit-related benefits.

All this also ties into the ‘coordination’ of CARICOM members’ foreign policies regarding how national interests and priorities of Member States play out in some international exchanges in relation to regional consensus. All this raises the stakes for CARICOM-AU summitry, but also CARICOM foreign policy broadly conceived. That said, CARICOM’s leadership and policy-makers should be applauded for their efforts thus far. Amid growing concerns about the diminution in the multilateral architecture and structural stresses in liberal internationalism, sending contemporary global governance (clinched nearly 30 years ago) reeling, they have taken a necessary step towards proactively strengthening the bloc’s hand in the pursuit of seemingly beneficial relations with like-minded states.

Notes on contributor

Dr. Nand C. Bardouille heads the Diplomatic Academy of the Caribbean in the Institute of International Relations (IIR), The University of the West Indies (The UWI) – St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago. Dr. Bardouille’s teaching and research focus are on International Relations and Comparative Politics, with a regional focus on the Caribbean. He specialises in and has published on small states' diplomacy, foreign policy, and international economic relations.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Ambassador Errol Humphrey, Ambassador Patrick I. Gomes, Ambassador Colin Granderson and Professor Timothy M. Shaw for their insightful comments and constructive advice on earlier drafts. Special thanks go to Ambassador Humphrey and Ambassador Gomes, who shared their expertise and provided invaluable perspective in discussions on aspects of this article. Helpful suggestions were also provided by the editors and reviewers of the Afronomicslaw symposium entitled ‘Prospects for Deepening Africa-Caribbean Economic Relations’. I also owe a debt of gratitude to interviewees. The usual disclaimer applies for any remaining errors and omissions.