August 30, 2021

Introduction

The COMESA Competition Commission (CCC) has been recognized as the most established regional competition authority so far in Africa. However, the CCC’s enforcement of the 2004 COMESA Competition Regulations (the “Regulations”) has not been easy. It has been marred with challenges. For instance, the launch of CCC –although established in 2004–faced backlash from some of the COMESA Member States, COMESA national competition agencies (NCAs), lawyers, and the business community even before it became operational. That is why it took almost a decade, in 2013, for CCC to commence enforcement of the Regulations.

Despite these challenges, on 14th January 2023, CCC will be celebrating a decade of existence. If so, how has CCC enhanced the enforcement of the regional competition laws and what lessons can young and emerging regional competition regimes (RCRs) learn from CCC? In this blog article, we discuss the strategies that CCC has adopted in building its authority and strengthening cooperation with NCAs and other stakeholders in the enforcement of the COMESA regional competition law.

The COMESA Competition Commission

CCC is established under Article 6 of the 2004 Competition Regulations (Regulations) and is based in Lilongwe, Malawi. Under Article 7 of the Regulations, CCC has the overall mandate of enforcing the Regulations. Generally, CCC is required to apply the provisions of the Regulations ‘with regard to trade between Member States and be responsible for promoting competition within the Common Market’. To do so, CCC monitors and investigates anti-competitive conduct within the COMESA Common market, reviews mergers and addresses consumer welfare concerns.

As established, CCC is a supranational regional competition regime (RCR) (see Büthe and Kigwiru, The Spread of Competition Law and Policy in Africa: A Research Agenda) expected to make binding and legally enforceable decisions. However, its jurisdiction is limited to conduct that affects or is likely to affect two or more COMESA Member States. Consequently, COMESA’s NCAs jurisdiction is limited to cases having local nexus and within their territorial boundary. Once an anticompetitive conduct or merger transaction is cross-border and affects two or more of the COMESA Member States, this falls under CCC’s jurisdiction. In this case, NCAs are required to cede autonomy to CCC as well as cooperate and coordinate with CCC in the enforcement of the Regulations.

Theoretically, sharing of competences between a regional competition regime (RCR) and NCAs seems feasible. However, in practice it is marred with challenges including the political unwillingness of NCAs to allow an RCR to assess mergers and investigate anti-competitive conduct arising from the domestic markets. Generally, supranational RCRs are not only intrusive into Member States domestic regulatory power, but they also regulate an inherently political and complex issue area, competition policy. Thus, there are many reasons why an NCA could be less likely to cede autonomy to an RCR including fear of loss over NCA’s long established regulatory power (see Tim Büthe ‘Supranationalism’). In merger transactions, the loss of merger fees at the national level could be a reason for NCAs to resist a regional level institution. Moreover, inadequate resources and limited awareness on competition laws is a challenge facing most of young regional and national competition agencies in the Global South.

It was expected that once established, CCC in cooperation with COMESA Member States and NCAs, could enforce the Regulations ensuring that no anti-competitive conduct could thwart the trade liberalization efforts within the COMESA Common Market. Unfortunately, the lag in time in launching CCC also resulted from its constituencies backlash.

Constituencies as defined by Tallberg and Zürn are actors that have an institutionalized political bond with an institution. Thus, they are bound by the institutional rules and Regulations. In the context of the COMESA Competition regime, these actors include the COMESA Member States, national regulatory agencies such as the NCAs, the COMESA residents and the market participants in the COMESA common market. These constituency actors have a general Treaty obligation to ensure that the provisions of the COMESA Treaty and Competition Regulations are implemented. For instance, Article 5 of the Competition Regulations places an obligation on COMESA Member States as follows:

“Pursuant to Article 5(2)(b) of the Treaty, Member States shall take all appropriate measures, whether general or particular, to ensure fulfilment of the obligations arising out of these Regulations or resulting from action taken by the Commission under these Regulations. They shall facilitate the achievement of the objects of the Common Market. Member States shall abstain from taking any measure which could jeopardize the attainment of the objectives of these Regulations”.

In the next section we briefly describe the backlash faced by CCC during its earlier years of existence.

The Backlash Against CCC’s Enforcement of the COMESA Competition Regulations

CCC’s Board of Commissioners vide COMESA Official Gazette Vol. 10 No.2 of 2004 as Decision No. 43 announced that CCC had commenced the enforcement of the Competition Regulations as from 14th January 2013. Regarding merger notifications, CCC advised members of the public to notify all transactions having a regional dimension (transactions affecting two or more COMESA Member States) to CCC. CCC insisted that, ‘once a notification is made to the Commission, there is absolutely no need to notify the same to the individual’ NCAs. Importantly, mergers having a regional dimension were to be notified to CCC, regardless of their size as the merger threshold was at zero.

On one hand, COMESA was applauded for introducing a regional competition policy in the region that could complement the increasing trade in the region, enhance predictability of doing business in the region and provide a regime that would apply to countries with no competition law like Uganda. In case an NCA believed that a merger had an appreciable effect within its market, it would request a referral of the merger from CCC to the NCA as per Article 24(9) of the Regulations. Thus, it was expected that, if CCC initiated an investigation on restrictive trade practices affecting trade between the COMESA Member States, NCAs would not initiate parallel investigations. Instead, they would cooperate and coordinate with the CCC. This would have eased the cost of doing business within the region, enhance legal certainty, and increase foreign investment. Indeed, CCC affirmed to the business community that:

‘One of the benefits of the regional competition law regime is that it introduces a 'one-stop-shop' for cross-border transactions, thereby easing the cost of doing business in COMESA as such transactions no longer need to be notified in two or more jurisdictions'

On the other hand, various stakeholders raised concerns on the ambiguity of CCC’s supranational power. CCC’s scope of authority in merger regulation and the applicability of the Competition Regulation, were the most controversial. It should be noted that the backlash against CCC began before 2013. As earlier attempts to launch CCC had faced contestations from some COMESA Member States, the COMESA Council of Ministers, the NCAs, lawyers and the business community. When interviewed by the American Bar Association on 28 March 2014, George Lipimile, the then CCC’s Chief Executive Officer, noted that the reason why it took so long before CCC began enforcing the Regulations was because:

‘…the idea of having a regional competition regime was very new to the Member States. Hence, it was difficult to lobby the necessary support from the Member States for them to subscribe financially to the establishment of the Commission. Consequently, the COMESA Secretariat's lack of funding could have been the main course for the delay in commencing the operations of the Commission. There might had been other factors like the non-availability of skilled manpower and material resources to establish the Commission’.

The major challenge regarded the applicability of the Competition Regulations in the domestic market and whether NCAs were bound. Some COMESA Member States and NCAs argued that unless the COMESA Member States domesticated the COMESA Treaty and the Competition Regulations, the Regulations had no direct applicability in the domestic market. However, the question whether Member States needed to domesticate the Competition Regulations was merely political. This provided an opportunity for NCAs to invoke parallel jurisdiction over similar mergers filed at the CCC, arguing that CCC did not enjoy exclusive jurisdiction over mergers with local nexus.

Some NCAs such as the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) argued that in the absence of domestication of the COMESA Treaty and its Regulations, the 2004 Competition Regulations had no legal applicability in the national markets. Thus, CAK was not bound. Invoking parallel jurisdiction, CAK made it clear that local firms, despite filing cross-border mergers with the CCC, were required to file with CAK too. The implication was that no merger that met COMESA and Kenya’s merger thresholds could be implemented in the specific markets without approval of the CCC and CAK respectively. This led to multiple notifications.

Moreover, NCAs’ backlash against CCC’s merger authority created confusion among the business community and lawyers. This confusion was also exacerbated by the zero-merger threshold, low competition awareness and limited competition culture. The reason why the business community and lawyers contested COMESA’s merger filing fees in 2013, was because it was deemed unreasonably high, especially for the small-sized market enterprises (SMEs). This potentially hindered the ability for SMES’ to regionalize and expand through mergers and acquisitions.

So, how did CCC address this backlash and what lessons can emerging RCRs in developing countries learn from CCC?

Addressing the Backlash: Prioritization and Strategic Actor Collaboration.

As a new regional institution, regulating an inherently political and complex issue area, backlash was inevitable. Competition law is inherently political because, it involves using political power to '(re)shape the operational, or distribution of benefits of a market'. It is also complex, as it requires legal and economic expertise to assess mergers and anti-competitive conduct. Yet, the capacity and capability of competition regulatory agencies in Africa is highly constrained due to limited resources. Also, in 2004, a regional level competition regime was novel. This meant that in order to build on its authority, CCC had to work on a constrained budget, create awareness and increase cooperation with NCAs, lawyers and the business community.

Consequently, CCC embarked on a number of strategies as described below:

a. Advocacy and Awareness

As a new regime, CCC prioritized creating awareness in and outside the region. Within the region, CCC noted the need to generate support for the creation of competitive markets for citizens of the Common Market to reap the benefits of, and contribute to the advancement of, integrated markets. CCC conducted national sensitization workshops in almost all the Member States (save for those countries where political unrest did not create safe environment for conducting such missions) and designed targeted advocacy missions for each group of stakeholders, being the government officials, consumer associations, business community, legal community. In addition, CCC organized regional workshops aimed to promote the understanding of the operations and implications of the Regulations.

Outside the Common Market, CCC has forged strong ties with its counterparts in the US, EU, and South Africa to ensure its legal instruments are aligned with international best practices and learn from mistakes and challenges experienced by others.

b. Collaboration with other Actors

CCC’s interaction with actors was strategic and varied. Although Member States had the power through the COMESA Council of Ministers to review the Competition Regulations and include an explicit provision that grants CCC exclusive jurisdiction over mergers, CCC was hesitant to adopt this political approach. In contrast, CCC continued to create awareness amongst the Member States to elicit support. During his interview with Clifford Chance in July 2013, six months after CCC was operationalized, Lipimile noted that CCC was more careful when engaging with Member States:

‘So far, the difference between enforcing at the national and regional levels is that at the regional level we tend to be more careful because we are dealing with member states. Issues of public interest become more sensitive than at national level, because there is a need for us as a new regional regulator to be accepted, and the only way you can be accepted is to be consistent, to be transparent and to have due process’.

With regard to NCAs, CCC opted for voluntary mechanisms through bilateral agreements and technical assistance. Thus, to date, CCC has entered into a Memorandum of Understandings (MoUs) with established NCAs in Kenya, Seychelles, Eswatini, Egypt, Madagascar, Malawi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mauritius, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The objective of these MoUs is to promote and facilitate cooperation and coordination between CCC and NCAs. Also, to reduce the possibilities and impacts of conflicts between CCC and NCAs. The MOUs have contributed to improving the working relationships between case handlers at the respective authorities, as evidenced by an increase in willingness and trust in sharing of information on cases of mutual interest and discussions on candidate theories of harm. A notable success arising from such cooperation frameworks has been the review of merger notification thresholds at national level in Kenya which led to the elimination of double notification of regional mergers to the Competition Authority of Kenya and CCC.

With regard to young NCAs in the region, CCC focused on providing technical and capacity building to Member states without competition laws to develop one. The objective was to enhance advocacy, strategic collaboration, and institutional strengthening. Thus, CCC facilitated the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Sudan, Seychelles, Madagascar, and Comoros tour visits to countries with established NCAs -Kenya, Mauritius, Malawi, Egypt, and Zambia- to learn best practices on setting and operationalization of its national competition authority.

The purpose of these study tours was to enable Member States with newly established authorities and those contemplating the setting up of a competition authority to appreciate the challenges commonly experienced in the set up and operationalisation of NCAs and practical solutions to remedy such challenges. The NCAs are a critical stakeholder for the effective enforcement of the Regulations and it has been a priority of CCC to promote strong enforcement of competition laws at national level, hence its dedication to building capacity for NCAs.

Beyond NCAs, CCC also coordinated with other actors in the region. Realizing the role of the media in creating awareness, CCC arranged regional business workshops inviting the media. By 2018, CAK had held six regional conferences inviting journalists within the region. This seeks to answer the question: How can national competition agencies (NCAs) build their regulatory capability in on. The objective was to educate the media on the objective of the Regulations and the role of CCC. As the media played a fundamental role in disseminating information. CCC also targeted lawyers, diplomats and Ministers of Trade.

c. Sharing Benefits

The intrusion of CCC into NCAs regulatory power, meant that NCAs lost not only the regulatory power but also on merger filing fees and fines imposed on market actors contravening the competition law. To ensure equitable redistribution of benefits, CCC adopted the Rule on COMESA Revenue Sharing of Merger Filing Fees. According to Rule 8, CCC retains 50% of the merger filing fees accrued in a merger transaction, and distributes the remaining 50% to the NCAs or the government where an NCA is lacking. CCC ensures that the share of the filing fees is proportional to the value of the turnover in each Member State relative to the total value of the turnover in the Common Market.

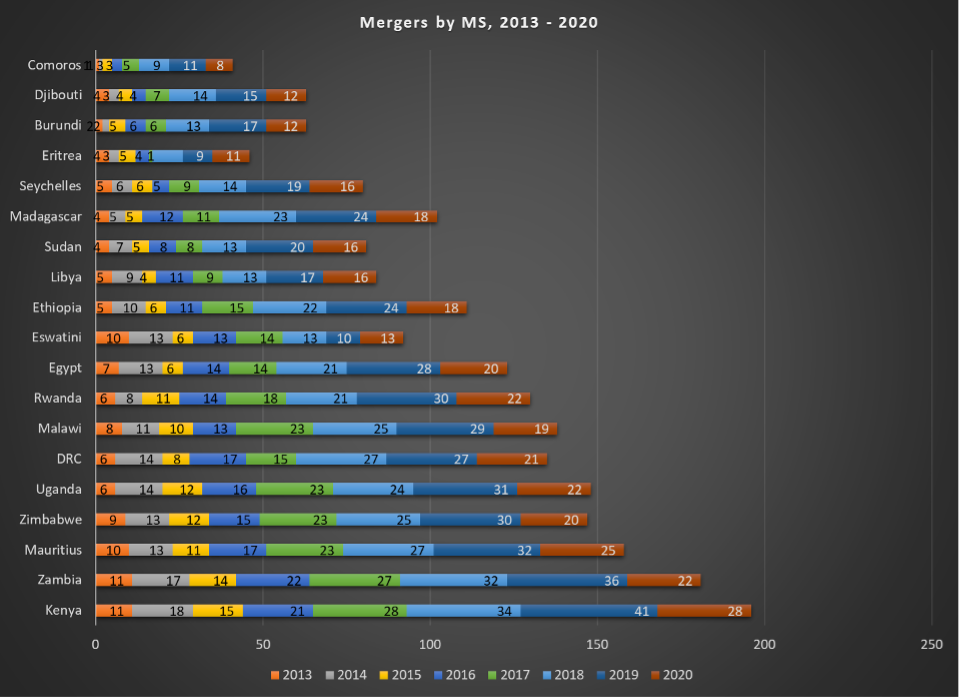

As COMESA countries are affected differently by merger transactions, the share of the merger revenue fees varies. As shown in the table below, Kenya, Zambia, Mauritius, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Malawi DRC, Rwanda, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Madagascar are most affected by merger transactions in that order.

COMESA Countries most affected by mergers between 2013-2020

Source: CCC, 2020

Key developments

There are a number of developments within COMESA that scholarly work has failed to bring to our attention, focusing more on the challenges facing RCRs. In addition to reducing on jurisdictional conflicts, the COMESA NCAs have been at the forefront in the regionalization of competition law. An indication that NCAs have recognized the need to support CCC. For instance, the Malawi Competition and Fair Trading Commission (CFTC), in 2016, engaged in consultations with the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, and the Ministry of Justice and Constitution Affairs to initiate domestication of the Competition Regulations.

In 2019, the Competition Authority of Kenya, enacted the Competition Rules, 2019 which provide that where a merger meets the COMESA regional dimension merger thresholds, undertakings shall merely inform the CAK in writing that a transaction has been notified to the COMESA Commission within 14 days of filing the notification to the COMESA Commission.

Currently, the CCC is working with the Competition Commission of Mauritius to ensure that there is a sound legal framework that support the interaction of the COMESA Competition Regulations and the Competition Act of Mauritius.

So, what lessons can young RCRs in developing countries borrow from COMESA?

Lessons for emerging regional competition regimes in developing countries

There are a number of lessons, emerging supranational RCRs in developing countries such as ECOWAS and EAC can learn from the CCC.

a. Advocacy

Competition law awareness increases recognition and acceptance of an institution. And because competition policy as a concept in developing countries is still young, RCRs should prioritize advocacy. Advocacy not only creates awareness, but could also increase competition culture. Competition culture enables stakeholders understand the benefits of having a regional level competition regime. Thus, RCRs should lobby stakeholders through advocacy to win the acceptance of the RCR by the business community, NCAs and the Member States.

b. Clear Scope of Authority

Supranational RCRs sharing competencies with NCAs need to ensure that their scope of authority is unambiguous. This increases clarity and reduces conflicts with NCAs. One way to do so, as was the case with CCC, is to have quantifiable merger thresholds. Meaningful merger notification thresholds to ensure that not all merger transactions are ceded from the national competition authorities to the RCR. Meaningful merger notification thresholds would also ensure that only mergers with regional significance are captured by the RCR thereby reducing the cost of doing of business.

c. Benefit Sharing Formula

An effective RCR should have in place a mechanism that ensures equitable redistribution of benefits to minimize on backlash. This is important because, in many cases, an NCA is required to cede autonomy over regulation of competition cases to the RCR. Some NCAs may resist such delegation even when the regional competition law requires them to do so. Established NCAs may fear losing their regulatory power, Additionally, merger filing fees and fines are a source of income for many NCAs, especially in developing countries. Thus, an NCA could resist an RCR simply because they fear losing on merger filing fees. However, such revenue sharing mechanism should be reached by all Member States and NCAs.

d. Reasonable Merger Filing Fees.

RCRs that regulate mergers in the region should adopt merger filing fees that are reasonable. Unreasonable merger filing fees could be reason why the stakeholders may not accept the application of the regional competition law as it may result in high cost of doing business. CCC faced backlash from business community and lawyers when its merger filing fees were high. This could have hindered SMEs from regionalizing through mergers and acquisitions. This led to CCC reducing its merger filing fees.

e. Strategic Stakeholder Engagement

Importantly, young RCRs in developing countries need to be strategic on how and which actors it should engage with. When faced with backlash, CCC entered in MoUs with NCAs. CAK which had resisted CCC’s jurisdiction over mergers emanating from the Kenyan market, no longer opposes CCC’s authority. An indication that indeed, voluntary mechanisms and advocacy can enhance compliance. Moreover, actors go beyond NCAs and Member States, as CCC interacted with the media, diplomats, lawyers and Ministers of Trade.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have shown that indeed RCRs are likely to face resistance. This is because, competition policy is inherently political and complex. It requires the constituencies to understand its benefits and costs. However, RCRs could reduce backlash by carrying out advocacy, ensuring their scope of authority is clear, sharing benefits accrued and strategically engaging with various stakeholders.